____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Save-The-Cedar League

8995 Loos Road, Crescent Spur, British Columbia, Canada V0J 3E0

Educational Report No. 4, May 2002

_______________________________________________________

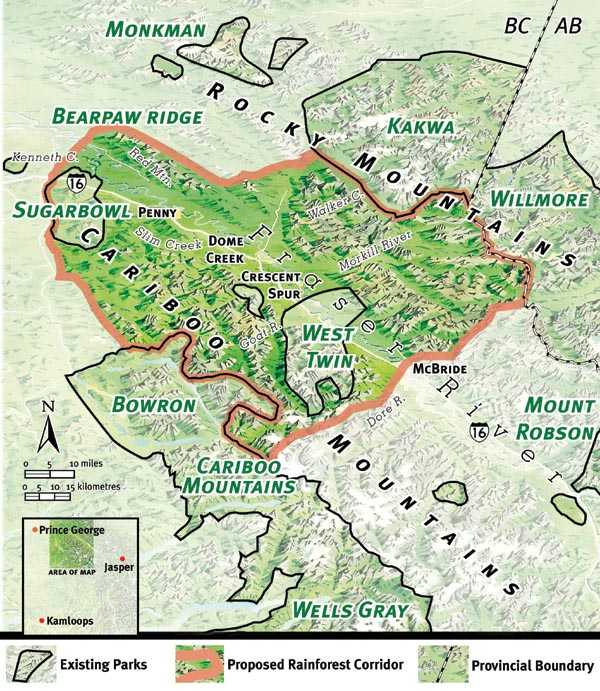

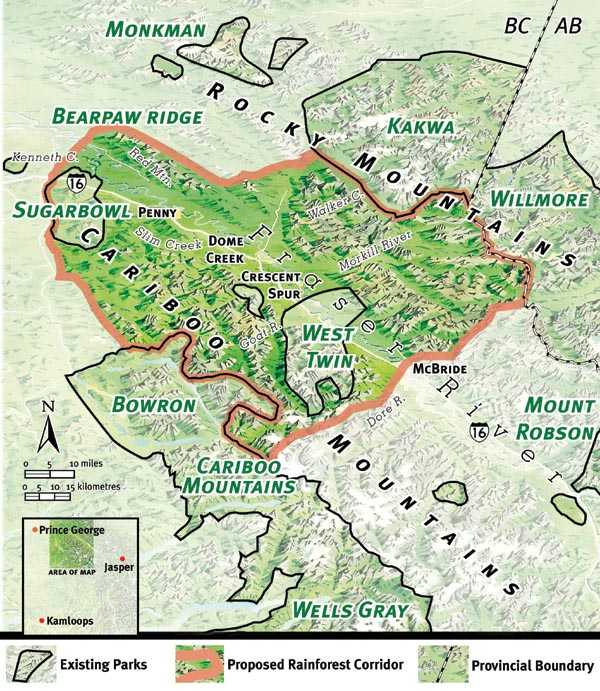

RAINFOREST CONSERVATION CORRIDOR FOR ROBSON VALLEY

Within the Rocky Mountain

Trench between the Rocky and Cariboo Mountains of East-Central British Columbia,

Canada, the mighty Fraser River nourishes an ancient rainforest matched nowhere

on earth. Massive Western Redcedar trees (Thuja plicata), some over 1200

years-old, 3.5 meters in diameter, and 45 meters high inhabit Robson Valley. The ancient forests of this valley contain the worldís most extensive example

of an inland rainforest in the Northern Hemisphere1.

Additionally, the Robson Valley is the only valley left in all of the Rocky

Mountains of the United States and Canada where grizzly bears still feed on

wild ocean-going salmon.

The ancient forests of this valley contain the worldís most extensive example

of an inland rainforest in the Northern Hemisphere1.

Additionally, the Robson Valley is the only valley left in all of the Rocky

Mountains of the United States and Canada where grizzly bears still feed on

wild ocean-going salmon.

Most rainforests are

Temperate-Coastal or Tropical, whereas the Robson Rainforest is Oroboreal: meaning

mountain-caused with boreal biome characteristics. The term "Antique Forest"

is now used to distinguish between ancient cedar-hemlock stands that have remained

ancient for more than 1000 years, versus those ancient stands that are only

as old as their oldest trees2.

The Antique Forest phenomenon is usually restricted to small glacial watersheds

on the windward slopes of the Columbia and Rocky Mountains of Southeastern BC.

Extensive Antique Forests occupy a major watershed only in the shadows of Mount

Robson, the highest peak in the Canadian Rockies (3954 meters), on the first

terrace of the Upper Fraser River, between Dore River and Kenneth Creek (Figure

1, left).

The largest clump of

ancient cedar known to exist in Robson Valley contains 20 trees over 250-years-old,

with some 1000 years old, forming a tight circle only 15 meters wide. Discovered

in 1999, we call this Primordial Grove (Figures 2-4, below). It is found in

the Ancient Cedar stands near Highway 16, between Slim and Driscoll Creeks.

Here several live ancient cedar trees grow out of the trunks of other live ancient

cedar trees, in the 180 million-year-old primitive tradition observed in the

closely-related redwoods (Sequoia). Basal shoots of the trunk grow genetically-superior

mature redwood trees when compared to seeds, root sprouts, other shoots, or

other layering phenomena3.

The rainforest in the vicinity of Primordial Grove supports a diverse Predator-Prey

ecosystem containing grizzly and black bear, gray wolf, cougar, lynx, wolverine,

coyote, and seven ungulate species.

NEW GRIZZLY BEAR SANCTUARY PROPOSED FOR THE ROBSON RAINFOREST

Where is the only valley left in all the Rocky Mountains of Canada and the United States where grizzly bears still feed on wild ocean-going salmon?

Long-term grizzly bear and Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) observations by Save-The-Cedar League (STCL), and DNA analysis on grizzly bear hairs by The Wildlife Conservation Society in 2000, confirmed that grizzly feed on wild ocean-going salmon only in Robson Valley, and nowhere else in all the Rocky Mountains! Salmon spawning grounds are visited by grizzly in July-September, up to 60 km deep into the Rocky Mountain headwaters from the Fraser River main stem. The salmon runs on Forget-Me-Not Creek and the Beaver/Holmes River extend near the Alberta/BC border of Robson Valley. Grizzly bear trails between both these spawning grounds and Willmore Wilderness Park probably mean that Alberta grizzly bears also feed on ocean-going salmon only in Robson Valley.

Many rainforest grizzly

feed on Devilís Club berries (Oplopanax horridus) during August-September.

They feed on Yellow Glacier Lily corms (Erythronium grandiflorum), Arctic

Lupine taproots (Lupinus arcticus), Columbian Ground squirrels (Spermophilus

columbianus), and the glacier lily corms the ground squirrels store in their

hibernation nests4,

before the bears hibernate. Some of the highest concentrations of grizzly bears

seen anywhere in BC can be observed feeding on these items every year during

a remarkable grizzly bear gathering near Red Mountain, on Bear Paw Ridge, in

Robson Valley. STCL observed 22 different grizzly foraging on Red Mountain in

less than two days during September 2000. At least 26 grizzly were seen in 1999,

and 22 others were seen in 1998 by author Jack Boudreau and associates (Figure

5, below--area outlined in red as "Antique Rainforest").

Some of the largest grizzly ever seen in BC were found near Red Mountain and Slim Creeks5,6. A huge black grizzly was called: "the biggest bear Iíve ever seen, a monster," as it was filmed in 1995. STCL also observed a huge black grizzly mating near Walker Creek 30 km away the same year. It was the largest and darkest grizzly we have ever seen, two feet taller at the shoulders than the female, and one foot taller than the largest grizzly we have seen anywhere in BC or Alberta, where we have seen about 200 grizzly over 20 years.

STCL has observed several grizzly commonly migrating among Walker, Slim, and Red Mountain Creeks, and Bear Paw Ridge, which all lie between Kakwa and Sugar Bowl/Grizzly Provincial Parks. We also observed grizzly movements between these areas and the Morkill, Goat, Forget-Me-Not, Snowshoe, and Ptarmigan watersheds. We documented the reduction in population numbers of grizzlies by 15% over the last decade in the Robson Valley Bioregion with these and other observations (see inset for Abstract7).

***************************************************************************************

Some Information on Grizzly Bear Ecology in Robson Valley and Surrounding Regions 1987-2000.

By Rick Zammuto, Ph.D., SEE ME Consultations, Crescent Spur, BC.

We have studied the distribution, abundance, range, movements, food, habits and other ecology of grizzly bears in the field for the last 12 years using bear sign and sightings throughout Robson Valley, the Prince George District to the vicinity of Purden Lake, portions of the North Thompson watershed, and in portions of Mount Robson and Jasper Parks. Tracks, scats, sightings, digs, rubbing sites, hairs, fur mats, ground scrapes, trails, partly-eaten or broken vegetation, claw marks, bedding sites, feeding sites, kill/cache sites, DNA hair analysis, literature, interviews, and other inventory methods were used to indirectly determine abundance, movement, migratory corridors, and the frequency and seasonality of habitat-use throughout the region. Old growth, riparian zones, Antique Rainforest, and salmon-eating grizzly at lower elevations were more intensively sampled in Robson Valley.

These data were used to roughly estimate the total number of adults inhabiting each watershed and the seasonal frequency of bear-use of each forest cover polygon, especially for Antique Rainforest. The most plausible conservation corridors through critical habitat and the evaluation of grizzly bears for umbrella, focal, key, flagship, or indicator species were also studied. Some effects of proximity to human habitation and industrial-use on bears, especially clearcuts, hunting, right-of-ways and other land uses were also determined.

Grizzly population size began at about half potential, generally declined 5-15% from 1987 to 1997, especially during 1992-1997, then a slight return to some former ranges occurred during 1998 and 1999 in Robson Valley (+2%). The Robson Valley is becoming known as the last site in the Rocky Mountains where grizzly still feed on wild anadromous salmon. It may also be the site of the largest population of low-land grizzly using the Inland Antique Rainforest. Benchmark areas, cross-valley corridors, and an Inland Rainforest Grizzly Bear Sanctuary are now being proposed by several scientists, conservation groups, and residents using these and other data.

In general, proximity to human habitation, clearcut logging, poaching, right-of-ways, and other factors are removing this slow-reproducing species at an alarming rate, and these factors include bear declines in Jasper and Mount Robson Parks, especially where bear ranges crossed Park boundaries and right-of-ways. Therefore, there is strong scientific support for the conclusions of Soule and Sanjayan8 (1998, Science 279:2060) and Woodroffe and Ginsberg9 (1998, Science 280:2126), that lack of enough protected area, human habitation, clearcutting disturbances, lack of effective conservation corridors, roads, and the lack of buffers around current protected areas will most likely lead to the extirpation of grizzly bears from large portions of Robson Valley over the next decade, unless new land-use proposals arise from the above and other information.

****************************************************************************************

The grizzly bear is an "umbrella species". When the

grizzlyís range is protected, 95% of the habitats of all species in the grizzlyís

range are also protected at the same time. For example, habitat for the dwindling

woodland caribou, bull trout, salmon, and goshawk is protected when grizzly

bear home ranges are protected. Therefore STCL proposes protection of the entire

Rainforest grizzly bear population of Robson Valley (Figure 6, below).

KEY VALUES WITHIN THE PROPOSED RAINFOREST CONSERVATION CORRIDOR

The proposed conservation corridor links Kakwa, Bowron, West Twin, Cariboo Mountains, Sugar Bowl/Grizzly, Erg Mountain, Willmore, and Ptarmigan Creek Provincial Parks through the Goat, Morkill, Hellroaring, Forget-Me-Not, Cushing, and Walker Watersheds, including Bear Paw Ridge. This area has some of the highest conservation values in BC:

Some of the oldest cedar known to exist anywhere in the Interior of BC;

The last watersheds in the entire Rocky Mountains where grizzly bears still feed on wild ocean-going salmon;

The highest density grizzly bear population in East-Central BC, with more than 150 grizzly bears, including the annual grizzly gathering site on Bear Paw Ridge;

Many Antique Rainforest patches, found on the unprotected portions of the Goat and Morkill Rivers, Walker, Dome, and Slim Creeks, and in the main Fraser River valley bottom between these watersheds;

The calving grounds for the southern-most-remaining Alberta caribou herd, the calving and wintering habitats of dwindling BC woodland caribou, and 6 other ungulate species: mountain goat, bighorn sheep, elk, moose, mule deer, and white-tailed deer;

Eight large predator populations: grizzly bear, black bear, gray wolf, cougar, wolverine, lynx, bobcat, and coyote;

A bottleneck wildlife corridor, used annually for migration by many large mammals, and up to 1500 spawning Chinook salmon, in the Morkill, Hellroaring, and Forget-Me-Not watersheds;

The highest water volume for a waterfall (Morkill Falls) in the region. Two other waterfalls dropping over 300 feet entering the Morkill River adjacent to Morkill Falls. (Grizzly feed on spawning salmon among the large boulders strewn along the magnificent raceway beneath these three falls);

Supports great blue heron, sandhill crane, western grebe, peregrine falcon, prairie falcon, surf scoter, northern goshawk, long-billed curlew, short-eared owl, and other rare birds;

The Upper Goat and Walker watersheds are the two last remaining undeveloped, unprotected watersheds in Southern BC over 400 km2 (150 mi2) in size with migratory salmon, and legendary bull and rainbow trout populations.

Conservation Biology Principles for the Rainforest Conservation Corridor

There are five principles from the science of Conservation Biology that are applicable to the proposed Rainforest Conservation Corridor. Application of all the principles listed may only be possible for Robson Valley and nowhere else.

1) The Antique Rainforest, found nowhere else in the world outside BC, is a centre of exclusively high biodiversity in Robson Valley. It has been in place with few stand-initiating events since glaciation, and is one of the most threatened ecosystems in BC. Therefore, Antique Rainforest qualifies as a "Flagship Special Element".

2) The Western Redcedar, living up to 1500 years-old, growing more than 12 feet wide, a source of nourishment for 260 birds and 62 mammals, producing some of the most unique and diverse food-webs in North America, qualifies as a "Keystone Species".

3) Chinook salmon, provide nutrients and energy to rainforest headwater ecosystems that are not available to the forest by other means. The Robson salmon stock is the longest-migrating and largest-bodied Chinook in BC, is presently being extirpated, and therefore qualifies as a "Flagship Focal Species".

4) Grizzly bear, bull trout, and mountain woodland caribou are premier umbrella, endangered, at risk, or vulnerable species, that qualify as "Premier Focal Species".

5) Mountain woodland caribou qualifies as the "Indicator Species" for these ancient forests since when the ancient forest disappears the endangered caribou also disappears.

KEY WILDLIFE SPECIES AND ENDANGERED HABITATS AT RISK OF DISAPPEARING

Protecting this ancient rainforest protects habitats for over 260 bird and 62 mammal species, including 20 large carnivores, ungulates, and other key species. One-fourth of the bird or mammal species at risk of disappearing from British Columbia are found in the ancient rainforest proposed for protection10 (Figure 6).

The 16 following watersheds, with hundreds of unprotected salmon and bull trout spawning grounds, would all become protected11:

Morkill, Hellroaring, and Forget-Me-Not;

Torpy, Walker, and Humbug;

Red Mountain, Hungary, Slim, Driscoll, and Dome; and

Ptarmigan, Goat, LaSalle, East Twin, and Snowshoe watersheds.

Biological connectivity would be conserved among 8 Provincial Parks:

Kakwa;

Sugar Bowl/Grizzly;

Bowron;

West Twin;

Erg Mountain;

Ptarmigan Creek;

Cariboo Mountains; and

Willmore Wilderness Park, Alberta.

Protecting this ancient rainforest would also protect representatives of 9 of the 11 wildlife habitats determined by government to be at risk of disappearing from British Columbia, including internationally significant old growth forests, wilderness areas, and winter range habitats. Moreover, the second most biologically productive (standing biomass per hectare) old growth forests in Canada12,13, and the highest diversity of native tree species (includes 11 conifers), found in any single forest of British Columbia13, would all be protected in this corridor .

NEW INTERBREEDING BETWEEN BLUE JAYS AND STELLERíS JAYS IN THE RAINFOREST

Eastern Blue Jays (Cyanocitta

cristata), were seen in the Rocky Mountain Trench of BC only during the

last 15 years, previously being found mainly East of the Rockies14.

Hybrid crosses between Eastern Blue Jays and Stellerís Jays (C. stelleri),

were first documented in the Robson Rainforest by STCL in 199615.

Hybrids are now regularly seen throughout the proposed conservation corridor

(Figures 7 and 8, below).

|

|

Hybrids typically have white throats,

chins, upper wing coverts and under tail coverts, and a large area of white around

their eyes. There is an overall light blue color over the whole body, especially

the wings, tail, chest and belly. The face, neck, nape, and lore regions always

have some Blue Jay blue to the tip of the crest (Figure 9).

Six rainforest Blue/Stellerís hybrids have been extensively

studied since 1996. Five exhibited both Blue Jay and Stellerís Jay vocals, and

one hybrid was observed to make only Stellerís vocals. This hybrid had less

striking plumage, half-way between the typical hybrids and normal Stellerís,

looking like a back-cross between a hybrid and normal Stellerís. Blue Jays,

Stellerís Jays, and hybrid Jays all exhibited pairing behaviors among each of

the other two types. We speculate the "half-way-hybrid" was most likely

formed when a "normal" hybrid mated with a normal Stellerís, producing

this additional hybrid-type. This possible back-cross may indicate that a new

species could be arising in the rainforest of Robson Valley!

Hybrids are seen most often near the confluence of the Fraser

and Morkill Rivers. The Morkill headwaters share some 30 km with the boundary

of Alberta, where Blue Jays are abundant. More study is needed to determine

the mating viability of hybrids and to determine if the migratory path of Blue

Jays into the Robson Rainforest was from Alberta, through the Morkill River

watershed. The southernmost woodland caribou herd in Alberta annually uses this

same pathway to calf in the Morkill watershed and to return to Alberta to winter.

The very rare Rose-Breasted Grosbeak (Pheucticus ludovicianus),

and Black-Headed Grosbeak (P. melanocephalus), annually observed

by STCL may also be hybridizing, but we have not collected enough information

or photographed them yet. A song similar to a Blue Grosbeak (Guiraca caerulea),

was thought to be one of these hybrids in 1994, but this bird looked more like

an immature Blue Grosbeak, normally found only in the Southern US. Additionally,

a brownish Grosbeak-like bird we have never seen anywhere else in North America

was watched singing in the rainforest for the first time in spring 2000; we

could not find a description of this bird in any field guide, nor could we find

its song on any recording!

OCEANIC SPECIES OBSERVED IN THE ROBSON RAINFOREST

Lichens that usually occur near oceans were first discovered in the ancient old growth of Robson Valley in the early 1990ís16,17. STCL later discovered that rainfall during the biologically-important growing-season (May-August) in Robson Valley was similar to that in the temperate rainforest on the West Coast of Vancouver Island, BC. Therefore, the rainfall for oceanic lichen species was similar for those same species found living in Robson Valley.

Several birds that usually only occur near oceans were observed in the Robson Rainforest during the last 10 years by STCL:

1) Pomarine Jaegers (Stercorarius pomarinus), were first seen in Crescent Spur from 1993-1998 by STCL and several others. These are large, oceanic, gull-like predators with hawk-like bills, slender meter-long, pointed wings, sharply bent at the wrist, and with a white flash on the outer-wing primaries. This 50 cm long bird suddenly but awkwardly changes course and fans its variably-shaped tail when flying near cedar trees, which the bird never encounters on the ocean or tundra, its normal habitat.

Pomarine Jaegers nested in the Cariboo Mountains, in Robson Valley during 1995, thousands of kilometers from their normal arctic tundra nesting range. Young of both dark and light color phases from this nest were observed begging a parent for food on the wing near the alpine of Zig-Zag Mountain.

Immature pomarine jaegers were observed 300 km away along the North Thompson River in 1984, and around inland lakes in the Chilcotin of West-Central BC in the early 1900ís18,19. We found no former records of the species in Robson Valley and they were listed as "hypothetical" in 1996 around Prince George20. Jaegers seemed to be following ravens in Robson, perhaps to rob them, as it does other birds while on the ocean and breeding grounds;

2) The large white Glaucous Gull (Larus hyperboreus), with translucent window-like openings on its wings, began appearing in flocks of all white individuals along the upper Fraser River during Spring 1997, especially during stormy weather. Glaucous gulls are usually found only in the Arctic during summer and along the St. Lawrence during winter. A few have been seen 300 kilometers to the North and South of Robson Valley in recent years18,19;

3) An immature Mew Gull (Larus canus), was seen several times in July 1999, which may indicate breeding for this species closer to Robson Valley than is currently documented; and

4) A hummingbird with a yellow-head, that could have been either an aberrant Annaís hummingbird (Calypte anna), usually a coastal species, or an aberrant Rufous hummingbird (Selasphorus rufus), was seen in Robson in 199021.

Perhaps the appearance of these normally oceanic species may indicate new movements of these species into the very wet, productive Antique Rainforest habitats of Robson Valley. Alternatively, there may not have been opportunity for previous bird surveyors to observe these species because they are too rare, indicating the techniques that have been used to survey birds missed their presence. More study is needed to determine the rainforest distribution of these normally oceanic species, so we incite all to be on the lookout for these and other species throughout the rainforest.

LOGGING TO DESTROY RAINFOREST BIODIVERSITY

All the remaining unprotected

ancient rainforest in Robson Valley has now been licensed to private logging

companies, despite the cautions of scientists, land-use plans, and local communities.

If the companies can sell cedar, all the remaining unprotected rainforest

on flat ground in Robson Valley will be gone in less than 8 years22.

"Old growth management areas" are proposed by government to exist

only in the inoperable areas on steep slopes, only if the loggers cannot reach

them. Short-sighted government and logging interests will destroy the long-term

functioning of this world-unique rainforest ecosystem, and few British Columbians

will benefit. For the short-term gain of a select few, at a huge loss to the

many, the forest industry plans to cut this world-class rainforest to tiny pieces,

degrading and diminishing this magnificent ancient rainforest, and altering

forever millions of years of biodiversity evolution at a great loss to the world.

HELP CHANGE THE TIDE OF RAINFOREST DESTRUCTION

You can change the tide of rainforest habitat destruction by

helping us preserve the critical rainforest connecting corridor between the

Rocky and Cariboo Mountains. The land presently protected is not enough to protect

the biodiversity of this world-class rainforest. Protected movement corridors

of complete ecosystems that connect protected habitats are necessary for survival

of all animals, plants, and lichens of the Robson Valley region. Protecting

critical grizzly bear habitat in the Robson Valley leads to protecting almost

all biodiversity, Antique Rainforest, and other natural features between the

Cariboo and Rocky Mountains at the same time. Before itís too late, help us

make a corridor of protection between existing parks, using the magnificent

biodiversity of the worldís most extensive inland rainforest in the northern

hemisphere (Figure 10).

LITERATURE CITED

1

Save-The-Cedar League. 1996. Bridge the Island Parks with Ancient Rainforest

Biodiversity. Educational Report Number 1.

2 Goward, T. 1996. The "Antique" Rainforests of the Robson Valley, In Save-The-Cedar League Educational Report Number 1.

3 Ball, E.A., D.M. Morris, and J.A. Rydelius. 1978. Cloning of Sequoia sempervirens from mature trees through tissue culture. In, Round Table Discussion: Multiplication in vitro díespeces ligneuses. G embloux, Belgium, pp. 181-226.

4 Shaw, W. T. 1926. The storing habit of the Columbian Ground Squirrel. American Naturalist 60:367- 373.

5 Boudreau, J. 1998. Crazy Manís Creek. Catlin Press, Prince George, BC, 196 pp.

6 Boudreau, J. 2000. Grizzly Bear Mountain. Catlin Press, Prince George, BC, 243 pp.

7 Zammuto, R. M. 2000. Some Information on Grizzly Bear Ecology in Robson Valley and Surrounding Regions 1987-2000. Paper Presented at the Robson Valley BC Ministry of Forests Grizzly Bear Workshop.

8 Soule, M. and M. Sanjayan. 1998. Conservation targets: Do they help? Science 279:2060.

9 Woodroffe, R. and J. R. Ginsberg. 1998. Edge effects and the extinction of populations inside protected areas. Science 280:2126-2128.

10 Save-The-Cedar League. 1997. Robson Valley Ecoguide. Educational Report No. 2.

11 Department of Fisheries and Oceans. 1990. Fish Habitat Inventory and Information Program. Stream Summary Catalogues. Department of Fisheries and Oceans, Vancouver, B.C.

12 Ketcheson, M., T. Braumandl, D. Meidinger, D. Demarchi, and B. Wikeem. 1991. Interior Cedar- Hemlock zone, p 168, In, D. Meidinger and J. Pojar (eds.). Ecosystems of British Columbia. BC Ministry of Forests Special Report No. 6.

13 Bradley, T. 1991. Old growth forests-literature review and initial methodology. Silva Ecosystem Consultants Report.

14 BC Conservation Data Center. 1996. Personal communications with Zoologist Syd Cannings.

15 Zammuto, R. M., 1997. Description and Film of Blue/Stellerís Hybrid Holotype from Robson Valley, Report to Royal BC Museum Curator Michael McNall, 7 September 1997.

16 Goward, T. 1995. Macrolichens of the oldgrowth forests of the Robson Valley. Robson Valley BC Ministry of Forests Report, 19 p.

17 Goward. T. 1994. Notes on oldgrowth-dependent epiphytic macrolichens in inland British Columbia, Canada. Acta Bot. Fenn. 150:31-38.

18 Godfrey, W. E., 1979. The Birds of Canada. Queenís Printer, Ottawa. National Museum Canada Bulletin 203, 428 pages.

19 Campbell, R. W., N. K. Dawe, I. McTaggart-Cowan, J.M. Cooper, G. W. Kaiser, and M. C. E. McNall. 1990. The birds of BC. Vol. 2. Non Passerines. Royal British Columbia Museum.

20 Prince George Naturalists. 1996. Checklist of North-Central BC Birds. Prince George, BC.

21 Royal British Columbia Museum. 1990. Personal communications with Zoologist R. Wayne Campbell.

22 TRC Cedar Ltd. 2001. 15-year logging plan map for 2001-2015, 1:50,000 scale. McBride, BC.

23 Bocking, R.C. 1997. Mighty River: A Portrait Of The Fraser. Douglas & McIntyre, Vancouver, BC, 294pp.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to our financial contributors to this conservation message: The Henry P. Kendall Foundation, The Wilburforce Foundation, and The Fanwood Foundation. We also thank Geri Fletcher (ImagePro Services) for layout, Eckhard Zeidler (Z-Point Graphics) for the panorama map, Dana Snyder, Ellen Snyder, and Dick Bocking for editorial assistance, and Clarence Boudreau and Daniel Norton for salmon updates. Ecoguide wildlife drawings copyright Matthew G. Wheeler; used by permission. Printed with recycled paper and vegetable inks.

HOW YOU CAN HELP STOP THE DESTRUCTION OF THE ANCIENT RAINFOREST

1) Join Save-The-Cedar League ($15/yr), and make a tax-deductible, charitable donation (charitable organization registration number 89089 2490 RR0001).

2) Call (800) 663-7867 or write, to connect with Members of the BC Legislative Assembly, Minister of Forests, Minister of Air, Land and Water, and the Premier at: The Parliament Buildings, Government of BC, Victoria, BC, V8V 1X4. Tell them you want the biodiversity and ancient rainforest of the Robson Valley protected from logging using Save-The-Cedar League's proposed Rainforest Conservation Corridor. Tell them to protect the Antique Rainforests of the Robson Valley for the present and future generations.

Remind the Premier that he made a commitment with STCL to create a network of reserves to sustain the Fraser River, when he endorsed the "Federal-Provincial Fraser River Action Plan Start-up Agreement" in 1992. Tell the Premier you want STCL's Rainforest Conservation Corridor to become a legislated reserve to sustain the Fraser River23 as he agreed was necessary.

3) Refuse to buy Redcedar wood products, shakes, posts, rails, or mulch. Only one cedar rail may come from some 500 year-old Redcedar, and many trees this age are cut down and burned without being used at all.

4) Ecotour the Robson Valley Rainforest with us, or use your own STCL member's copy of our Robson Valley Ecoguide, containing vertebrate abundance and habitats used, directions to special ecological sites, hiking trails, old growth driving sites, waterfalls, lakes, and salmon spawning grounds.

5) Get a VCR copy of our Rainforest Grizzly Bear TV documentary to show your friends the grizzly gathering on Bear Paw Ridge ($11 donation).

6) Elect politicians to your local, regional, provincial, state, and federal governments who support protecting Robson Valley's ancient rainforest.

7) Actively participate to protect ancient forests and habitats of endangered species.

Your Name: ___________________________________________

Mailing Address: ___________________________________________

City/Town: ___________________________________________

Province/State: ___________________________________________

Postal/Zip Code: ___________________________________________

Email Address: ___________________________________________

Phone/Fax: ___________________________________________

Enclosed is $15 for membership in Save-The-Cedar League and a tax-deductible donation of $____________.

Published by Save-The-Cedar League (2002), 8995 Loos Road, Crescent Spur, BC

V0J 3E0, Email: stcedarl@aol.com, Website: www.savethecedarleague.org.

All rights reserved.

The ancient forests of this valley contain the worldís most extensive example

of an inland rainforest in the Northern Hemisphere1.

Additionally, the Robson Valley is the only valley left in all of the Rocky

Mountains of the United States and Canada where grizzly bears still feed on

wild ocean-going salmon.

The ancient forests of this valley contain the worldís most extensive example

of an inland rainforest in the Northern Hemisphere1.

Additionally, the Robson Valley is the only valley left in all of the Rocky

Mountains of the United States and Canada where grizzly bears still feed on

wild ocean-going salmon.